Why Your Supplier's 8-Week Lead Time Quote Means Different Things Depending on Who Owns the Factory

Two suppliers quote identical 8-week lead times for custom vacuum bottles. One delivers on schedule, the other is three weeks late. The difference isn't capacity or materials—it's who actually controls the production line.

A Singapore-based technology firm placed two identical orders last quarter—1,000 custom stainless steel vacuum bottles with laser-engraved logos for their annual corporate event. Both suppliers quoted eight weeks from order confirmation to delivery. The specifications were identical down to the pantone color of the powder coating. The purchase orders were signed on the same day. Yet Supplier A delivered in week eight as promised, while Supplier B's shipment arrived in week eleven, forcing the client to reschedule their event and pay premium rates for last-minute venue changes.

The procurement manager who handled both orders assumed the delay was due to material shortages or unexpected quality issues—the usual suspects when timelines slip. But when we reviewed the production records, materials arrived on schedule for both suppliers, and neither order failed inspection. The difference wasn't in what happened during production. It was in who controlled the production line in the first place.

Supplier A operated their own factory. When a larger client's order came in during week four and threatened to push the Singapore order back, the production manager extended two evening shifts and reallocated three technicians from a lower-priority project. The order stayed on track. Supplier B was a trading company. When the same scenario occurred at the factory they had subcontracted, they had no authority to adjust the schedule. The factory prioritized its own direct clients—companies that placed regular orders year-round—and the Singapore order was pushed to week ten. By the time Supplier B's account manager learned about the delay, it was too late to switch to another factory without starting the entire production process over.

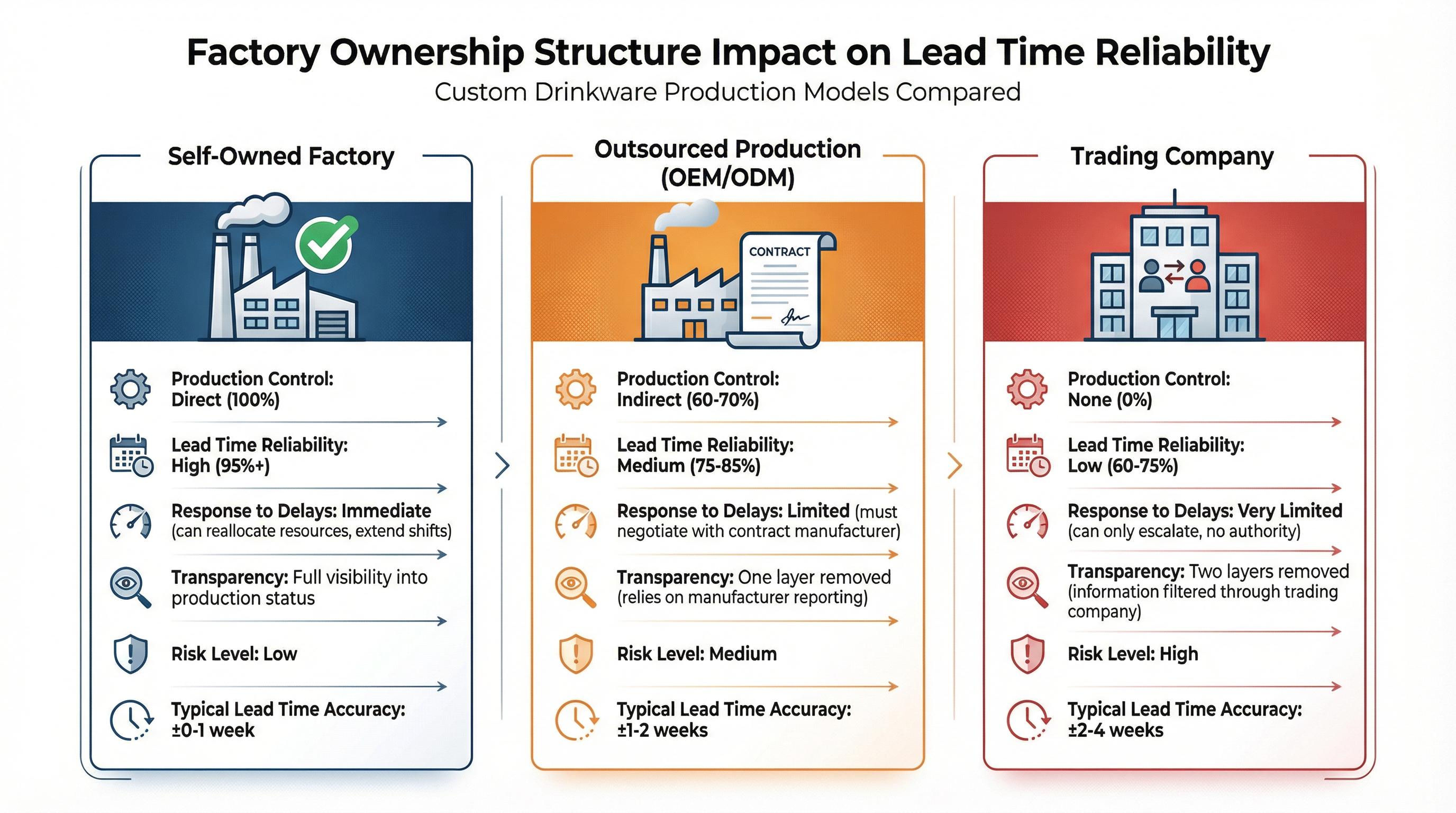

This scenario reveals a misjudgment that occurs repeatedly in corporate procurement, yet it is rarely discussed in lead time planning conversations. Buyers assume that when a supplier quotes an eight-week lead time, that figure represents a commitment backed by production control. In practice, the reliability of that quote depends entirely on whether the supplier owns the factory, contracts with a manufacturer they don't control, or acts as a middleman with no direct relationship to the production floor at all. Understanding the full production timeline and who controls each stage requires visibility into not just the steps involved, but the authority structure that governs those steps.

When a buyer places an order with a self-owned factory, they are entering into a direct relationship with the entity that controls capacity allocation, shift scheduling, and resource prioritization. If a delay threatens the timeline, the factory can make internal adjustments—reassigning workers, extending hours, or pausing lower-priority projects—to protect the commitment. The production manager answers to the same organization that made the promise to the client. There is no intermediary to negotiate with, no external party whose priorities might conflict with the buyer's timeline.

When a buyer places an order with a supplier that outsources production to a contract manufacturer, the relationship becomes indirect. The supplier negotiates for capacity with a factory that also serves other clients, including direct buyers who may have longer-standing relationships or larger order volumes. If the factory's capacity becomes constrained—whether due to an unexpected surge in orders, equipment downtime, or labor shortages—the contract manufacturer must decide which clients to prioritize. In that decision, the supplier who outsources production has less leverage than the factory's direct clients. The factory's incentive is to protect its own branded products and its most valuable long-term relationships. The outsourced order, especially if it is a one-time or small-volume purchase, is more likely to be delayed.

When a buyer places an order with a trading company, the relationship becomes doubly indirect. The trading company does not manufacture anything. It acts as an intermediary, sourcing products from factories it does not own and does not control. The trading company's value proposition is consolidation—they aggregate orders from multiple buyers, negotiate with multiple factories, and handle logistics and export documentation. But this consolidation comes at the cost of production control. When a delay occurs at the factory level, the trading company has no authority to intervene. They cannot reallocate resources, adjust schedules, or prioritize the buyer's order. They can only escalate the issue to their contact at the factory, who may or may not have the authority or willingness to make changes. In many cases, the factory does not even know the identity of the end buyer—they only know the trading company, which may be managing orders for dozens of other clients simultaneously.

The issue is not that trading companies or outsourced production models are inherently unreliable. Many trading companies have strong relationships with factories and can secure capacity more efficiently than a buyer could on their own, particularly for small or one-time orders. The issue is that the lead time quote provided by a trading company or an outsourced supplier is not backed by the same level of control as a quote from a self-owned factory. When a self-owned factory says "eight weeks," they are committing to a timeline they can directly manage. When a trading company says "eight weeks," they are estimating a timeline based on their experience with a factory they do not control, and that estimate assumes the factory will prioritize their order at the level they expect.

In practice, this is often where lead time decisions start to be misjudged. Buyers compare quotes from multiple suppliers, see identical lead times, and assume the quotes are equivalent. They may even favor the trading company's quote because the per-unit price is slightly lower, not realizing that the lower price reflects the trading company's lack of direct control over production. The buyer does not ask whether the supplier owns the factory, whether they have a contract manufacturing agreement, or whether they are simply acting as a middleman. The assumption is that "eight weeks" means the same thing regardless of who is providing the quote.

Three months ago, a procurement lead at a Singapore fintech firm contacted me after their order for 1,200 custom vacuum bottles with food-grade silicone lids was delayed by four weeks. The supplier—a trading company they had worked with once before—had quoted ten weeks from order confirmation to delivery. The order was placed in early November for a January corporate event. By mid-December, the supplier informed them that production had not yet started because the factory was prioritizing orders for clients with annual contracts. The fintech firm had no recourse. They could not contact the factory directly because the trading company had not disclosed which factory was producing the order. They could not switch suppliers because custom tooling for the silicone lids had already been paid for. They could only wait, and by the time the bottles arrived in late January, the event had already taken place. The company distributed mismatched bottles from a local supplier at the event and used the custom bottles as a secondary giveaway two months later.

The order was placed during what I call the "double jeopardy" window—the overlap between Q4 capacity constraints and the pre-CNY factory closure period. Orders placed in this window face compounding delays from two separate capacity shocks. But even outside peak season, the structural issue remains. A trading company's lead time quote is an estimate, not a commitment backed by production authority. When capacity becomes constrained for any reason—unexpected equipment failure, labor shortages, a surge in orders from higher-priority clients—the trading company's orders are the first to be delayed.

The reason this happens is not because trading companies are dishonest or incompetent. It happens because the factory's incentive structure does not align with the trading company's promises. The factory's priority is to maximize utilization of its own capacity while protecting its most valuable client relationships. Direct clients—companies that place regular orders, pay on time, and provide consistent volume—receive priority when capacity is constrained. Contract manufacturing clients receive secondary priority, because the factory has a formal agreement with them and wants to maintain that relationship. Trading company orders receive the lowest priority, because the factory has no direct relationship with the end buyer and no guarantee of future business.

This prioritization logic is rarely disclosed to buyers. When a trading company provides a lead time quote, they do not explain that the quote assumes the factory will treat their order as a medium-priority project, or that the timeline could extend by two to four weeks if the factory receives higher-priority work during the production window. The buyer assumes the quote reflects a commitment, when in reality it reflects an optimistic estimate based on normal conditions.

The practical consequence of this misjudgment is not just delayed delivery. It is the inability to respond when delays occur. When a self-owned factory encounters a delay, the buyer can escalate directly to the production manager or factory owner, who has the authority to make decisions. When an outsourced production model encounters a delay, the buyer can escalate to the supplier, who can then escalate to the contract manufacturer. There is at least a formal relationship and a shared interest in maintaining the business partnership. When a trading company encounters a delay, the buyer can escalate to the trading company, but the trading company has limited leverage with the factory. They can ask for updates, they can request prioritization, but they cannot compel the factory to act. The factory's response depends entirely on the strength of the trading company's relationship with that particular factory contact, and on whether the factory perceives any risk to future business if they ignore the request.

In some cases, the trading company does not even disclose the delay until it is too late to mitigate. Because they are one step removed from production, they rely on the factory to provide status updates. If the factory does not proactively communicate that an order has been deprioritized, the trading company may not learn about the delay until the original delivery date has already passed. By that point, the buyer's options are limited. They can wait for the delayed shipment, they can cancel the order and forfeit any deposits or tooling costs, or they can accept a partial shipment and source the remaining units elsewhere. None of these options are ideal, and all of them could have been avoided if the buyer had understood the structural limitations of the trading company model before placing the order.

The challenge for buyers is that ownership structure is not always transparent. Trading companies do not advertise themselves as middlemen with no production control. They present themselves as suppliers, and they provide quotes that look identical to quotes from self-owned factories. The buyer must ask specific questions to determine who actually controls production. Does the supplier own the factory? If not, do they have a formal contract manufacturing agreement? If not, what is their relationship with the factory, and how much influence do they have over production scheduling? These questions are rarely asked during the quotation process, because buyers assume that any supplier providing a lead time quote has the authority to deliver on that timeline.

The other challenge is that trading companies and outsourced production models do offer legitimate value in certain scenarios. For small orders—below the minimum order quantity of most self-owned factories—a trading company may be the only viable option. For buyers who lack experience with international logistics, a trading company's consolidation and export services can simplify the process. For orders that require sourcing from multiple factories—such as a corporate gift set that includes bottles, mugs, and tumblers from different manufacturers—a trading company can coordinate the entire supply chain. The issue is not that these models should be avoided entirely. The issue is that buyers need to understand the trade-off they are making when they choose a supplier without direct production control.

When lead time reliability is the primary concern—such as for a time-sensitive corporate event, a product launch, or a seasonal promotion—the buyer should prioritize suppliers with direct ownership of the production facility. When cost is the primary concern, or when the order is small enough that self-owned factories will not accept it, a trading company or outsourced model may be appropriate, but the buyer should add buffer time to the quoted lead time to account for the structural limitations of that model. A self-owned factory's eight-week quote can be treated as a reliable commitment. A trading company's eight-week quote should be treated as an optimistic estimate, and the buyer should plan for ten to twelve weeks to account for potential delays.

The distinction matters most when comparing quotes from multiple suppliers. If Supplier A (self-owned factory) quotes ten weeks and Supplier B (trading company) quotes eight weeks, the buyer should not assume that Supplier B is faster. Supplier A's ten-week quote reflects the time they need to complete production under their direct control. Supplier B's eight-week quote reflects the time they estimate the factory will need, assuming the factory prioritizes their order at the level they expect. In a normal scenario, Supplier B may deliver in eight weeks. In a constrained scenario—which occurs more often than buyers realize—Supplier B may deliver in twelve weeks, making Supplier A the faster and more reliable option despite the longer quoted timeline.

This is not a theoretical concern. It is a pattern I have observed repeatedly across twelve years of managing both self-owned and outsourced production lines for custom drinkware. The buyers who experience the fewest delays are not the ones who choose the shortest quoted lead time. They are the ones who ask which supplier has direct control over production, and who adjust their expectations accordingly. The buyers who experience the most delays are the ones who assume all lead time quotes are equivalent, and who prioritize cost or convenience over production control.

The misjudgment is understandable. Lead time is presented as a single number—eight weeks, ten weeks, twelve weeks—and buyers naturally assume that number represents a comparable commitment across all suppliers. But in reality, that number represents different levels of reliability depending on who is providing it. A self-owned factory's lead time is a commitment backed by production authority. An outsourced supplier's lead time is an estimate backed by a contractual relationship. A trading company's lead time is a projection backed by nothing more than their experience with a factory they do not control. All three may quote the same timeline, but only one has the structural capability to deliver on that timeline when conditions change.

For buyers who want to avoid this misjudgment, the solution is not to avoid trading companies or outsourced production models entirely. It is to ask the right questions before placing the order, to understand the ownership structure and production control limitations of each supplier, and to adjust lead time expectations accordingly. When timeline reliability is critical, prioritize suppliers with direct ownership of the production facility. When cost or consolidation is the priority, use trading companies or outsourced models, but add buffer time to the quoted lead time and maintain direct communication throughout the production process. And when comparing quotes, do not assume that identical lead times represent equivalent reliability. Ask who owns the factory, who controls the production schedule, and what recourse you have if delays occur. The answers to those questions will tell you more about lead time reliability than the number on the quote sheet ever will.

Related Articles

Why Your Supplier's 8-Week Lead Time Quote Doesn't Match the 10-Week Reality You Experience

When comparing supplier quotes for custom drinkware, buyers often assume "lead time" is a standardized metric like MOQ or unit price. In practice, one supplier's "8-week lead time" might mean production completion, while another's means delivered to your warehouse—a difference that can derail corporate gifting deadlines.

Why Your Supplier's 8-Week Lead Time in March Becomes 11 Weeks in October

A Singapore-based technology firm learned this lesson the expensive way last year. In March, they ordered 800 custom stainless steel bottles with their company logo for an internal product launch. The...

Why Your Supplier's 8-Week Lead Time Assumes Material Availability You Don't Actually Have

A Singapore fintech firm's CNY gifting timeline collapsed when their supplier's 8-week lead time didn't account for food-grade silicone seal procurement delays. The bottles arrived six weeks after Chinese New Year. This scenario reveals a misjudgment that occurs repeatedly in custom drinkware procurement: buyers assume lead time quotes include all material procurement phases, when suppliers quote timelines assuming standard material availability—a variable, not a constant.

Interested in Custom Drinkware?

Contact our team to discuss your requirements and receive a personalized quote for your corporate gifting needs.